|

|

|

09/29/2018 |

|

|

FRACTALS See http://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Mandelbrot+fractal+tour+guide Also see http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mathematics-ramanujan/ and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-similarity and also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fractal and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaos_theory In October 1992, when I was President of the Society of Actuaries, I had a video presentation of pictures of fractals and some background at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Actuaries. Robert Devaney developed the script. See Chaos video, but start about 40% of the way through. (OOPs is copywrite protected so will only play on my computer) If interested, read Don's Presidential Address. See Robert Devaney and chaotic systems and fractals at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6QIhaDvTHXk and http://math.bu.edu/people/bob/ Harlan Brothers articles on Mandelbrot and Fractal Music. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-SJvJK3r3I Also info from David David Richeson: Division by Zero Math Crafts: Salt Designs, Newton Snowflakes, Fractal Christmas Trees, Paper Pentagons, and Flip Books Posted by Dave Richeson on December 18, 2017 I have had a crafty late fall and early winter. I’ve been good about posting my crafts on Twitter, but not so good at blogging about them. So, I’ve collected them all and will share them all here in one blog post. The Geometry of Salt I came across this neat pdf by Troy Jones about using salt to do geometry. So, over Thanksgiving break I got my kids and their cousins together to do a little mathematics. We cut various shapes out of paper, propped them up on glasses, and poured salt over them. The salt is a natural bisector. The ridges can be used to bisect angles and to find the locus of points equidistant from two curves. We had fun making triangle centers, Voronoi diagrams, and conic sections. I had a good time thinking about why this worked (it is a fun exercise to see why these ridges form the various conic sections).

. Paper Pentagon In a recent paper by John Sharp I learned about tying a strip of paper into a regular pentagon. It goes back to ‘Tom Tit,’ which was the pen-name of Arthur Good (1853–1928).

Newton Snowflake The American Institute of Physics gave templates to make physics-related snowflakes. I used their template to make this Isaac Newton snowflake. (As cool as it is, it doesn’t have six-fold symmetry like a true snowflake.) They also have a crystallography and a Nikola Tesla snowflake.

Flip Book I have been wanting to make a mathematical flip book for a long time. Yesterday was the day that I made it happen. My 13-year old son and I figured out how to do it using the Adobe suite (my son is becoming a self-taught Adobe wiz). I started by creating the first four stages of the Koch snowflake using Illustrator. My son imported them into After Effects and had them morph from one to the other. He used Media Encoder to export them as an animated gif:

Then we exported the frames of the gif as 90 separate images. I printed them on card stock with nine per page (here’s a pdf). I cut them out and used a binder clip to hold them together. It seemed like 90 frames was perhaps too many, so I took every other frame and made two books of 45 frames. Those worked well. Lastly, I put the two books back to back and took following video of the triangle turning into a snowflake turning back into a triangle. I’m excited to make more flip books. Fractal Christmas Trees I found this blog post, which has instructions on how to make a fractal Christmas tree. I made one and thought it looked great. In fact, it folds up nicely into a card. So my daughter made one to give to her teacher.

Dave Richeson

Professor of

Mathematics

Dickinson College

My book

Euler's Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology

https://divisbyzero.com/ Recent Posts

Top Posts

|

Professor of Mathematics (2000)

| General Info | |

| Course Info |

![]()

His research involves the study of dynamical systems from a topological viewpoint, the history of mathematics (especially the history of geometry and topology), and recreational mathematics. He is interested in promoting expository mathematical writing.

| B.A., Hamilton College, 1993 | |||

M.S.,

Northwestern University, 1994

|

Ph.D., 1998

https://divisbyzero.com/

Read about at https://divisbyzero.com/research/eulers-gem/ | |

"Euler's Gem is one of the most elegant popular mathematics books I have read, a lovely exposition of some fascinating material which could be enjoyed by everyone from school students and lay readers to potential mathematicians. . . . Every school library should have a copy of Euler's Gem and it would be a great present for an otherwise curious student under-challenged or unexcited by the mathematics they are doing.

Mandelbrot Sets See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ma6cV6fw24 Also see discussion by Mandelbrot at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ay8OMOsf6AQ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mandelbrot_set and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=56gzV0od6DU

Julia Sets See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2AZYZ-L8m9Q and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mg4bp7G0D3s

Newton Fractal See http://vimeo.com/9770779

Serpenski and other results See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DO8yFGbbGmg

FIBONACCI SERIES See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjSHVDfXHQ4

The first two terms are 1 and 1. Then use the formula

![]()

The first 21 Fibonacci numbers Fn for n = 0, 1, 2, ..., 20 are:

| F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 | F12 | F13 | F14 | F15 | F16 | F17 | F18 | F19 | F20 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 34 | 55 | 89 | 144 | 233 | 377 | 610 | 987 | 1597 | 2584 | 4181 | 6765 |

These numbers also give the solution to certain enumerative problems. The most common such problem is that of counting the number of compositions of 1s and 2s that sum to a given total n: there are Fn+1 ways to do this. For example F6 = 8 counts the eight compositions:

1+1+1+1+1 = 1+1+1+2 = 1+1+2+1 = 1+2+1+1 = 2+1+1+1 = 2+2+1 = 2+1+2 = 1+2+2,

all of which sum to 6−1 = 5.

Golden Ratio is the only number that is one more than its resiprocal. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_ratio

The Fibonacci numbers have a closed-form solution. It is known as Binet's formula:

![]() where

where

![]()

Coin Game You have a pile of coins, and you can take up to and including twice what your opponent took last time…uses a winning strategy of leaving your opponent on a Fibonacci number or on the sum of two or more Fibonacci numbers. The person who picks up the last coin wins. On your first turn you can’t take all.

Start with 11 coins. Take 3, leaving 8 and you win, as 8 is a Fibonacci number.

Start with 12 coins. Take 4 and the other guy can take 8 and you lose. So reduce the pile to the sum of two Fibonacci numbers 8 +3 = 11 and take 1 reducing the 12 to 11. Your opponent can now take 1 or 2. If he takes 1, you take 2 and he has 8 to choose from. If he takes 2, you take 1 and he has 8 to choose from. Both are bad.

Whatever he chooses, say 2, you take 1 and leave him with 5. He can take 1 or 2. If he takes 1, you take 1… leaving him with 3. He can take 1 or 2…and you take what’s left.

BINARY NUMBERS

The modern binary number system was invented by Gottfried Leibniz in 1679.

|

Nim The traditional game of Nim used three rows of 3, 4, and 5 coins. On your turn, you can take any number from only one row. The person to pick the last coin wins. The winning strategy uses the Binary System to matched up pairs of powers of 2's.

3 = 2 + 1, 4 = 4, 5 = 4 +1 The person who goes first will win by taking 2 from the 3 pile to create matches.

If the game was four rows of 8, 13, 17, and 20:

20 = 16 + 4, 17 = 16 + 1, 13 = 8 + 4 + 1, 8 = 8 The person going first loses as we have matches

If the game was five rows of 5, 6, 7, 8, 10:

10 = 8 + 2, 8 = 8, 7 = 4 + 2 + 1, 6 = 4 + 2, 5 = 4 + 1 The person who goes first will win Take 2 from 5 pile, leaving 2 and 1.

The name is probably derived from German nimm meaning "take [imperative]", or the obsolete English verb nim of the same meaning.

Wythoff's game is a two-player mathematical game of strategy, played with two piles of counters. Players take turns removing counters from one or both piles; in the latter case, the numbers of counters removed from each pile must be equal. The game ends when one person removes the last counter or counters, thus winning.

Martin Gardner claims that the game was played in China under the name 捡石子 jiǎn shízǐ ("picking stones"). The Dutch mathematician W. A. Wythoff published a mathematical analysis of the game in 1907.

The Last Biscuit game is played by removing cookies from two jars, either from a single jar, or the same number from both jars. This game is also called the Puppies and Kittens game.

The strategy of winning Wythoff's Nim is to reduce the piles to a number pair.. If the starting pile numbers are safe, the first player loses. He is certain to leave an unsafe pair of piles, which his opponent can always reduce to a safe pair on his next move. If the game begins with unsafe numbers, the first player can always win by reducing the piles to a safe pair and continuing to play to safe pairs.

Let us take the safe pairs in sequence, starting with the pair nearest 0/0, and arrange them in a row with each smaller number above its partner, as in the table below. Above the pairs write their "position numbers." The top numbers of the safe pairs form a sequence we shall call A. The bottom numbers form a sequence we shall call B.

| Position (n) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| A | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 |

| B | 2 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 26 | 28 | 31 | 34 | 36 | 39 |

You cannot win with 21, 34. a) If you take 6 from the 34 pile leaving 21, 28 your opponent will take 4 from the 21 pile leaving you with 17, 28. b) If you take 7 from both piles leaving 14, 27 your opponent will take 4 from the 27 pile leaving you with 14, 23.

You cannot win with 21, 34. a) If you take 6 from both piles leaving 15, 28 your opponent will take 19 from the 28 pile leaving you with 9, 15. b) If you take 7 from the 34 pile leaving your opponent with 21, 27 your opponent will take 12 from each pile leaving you with 9, 15.

The two sequences, each one strictly increasing, have so many remarkable properties that dozens of technical papers have been written about them. Each B number is the sum of its A number and its position number. If we add an A number to its B number, the sum is an A number that appears in the A sequence at a position number equal to B. (An example is 8 + 13 = 21. The 13th number of the A sequence is 21.)

Can we generate the sequences by a recursive algorithm that is purely numerical? Yes.

Start with 1 as the top number of the first safe pair. Add this to its position number to obtain 2 as the bottom number. The top number of the next pair is the smallest positive integer not previously used. It is 3. Below it goes 5, the sum of 3 and its position number. For the top of the third pair write again the smallest positive integer not yet used. It is 4. Below it goes 7, the sum of 4 and 3. Continuing in this way will generate series A and B.

There is a bonus. We have discovered one of the most unusual properties of the safe pairs. It is obvious from our procedure that every positive integer must appear once and only once somewhere in the two sequences.

Is there a way to generate the two sequences nonrecursively? Yes. Wythoff was the first to discover that the numbers in sequence A are simply multiples of the golden ratio rounded down to integers! (He wrote that he pulled this discovery "out of a hat.")

Also see: http://www.fq.math.ca/Scanned/17-3/hoggatt.pdf

SYMMETRY and ITERATION See www. rmmsmsp.ucdenver.edu/instructormaterial/geometry-daisies.pps

Scientists strive to find mathematical patterns. However, Sir Francis Bacan said: "There is no beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion." Since beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder, are the most beautiful creations short lyrics or long symphonies?

David Wells said we might conclude that the beauty of the Mandelbrot set is "romantic"

Hardy said: "A mathematician, like a painter or poet, is a maker of patterns. If his patterns are more permanent than theirs, it is because they are made with ideas." Hardy also hoped that "nothing he had ever discovered would have any practical use.

Paul Erdős said, "Why are numbers beautiful? It's like asking why is Beethoven's Ninth Symphony beautiful. If you don't see why, someone can't tell you. I know numbers are beautiful. If they aren't beautiful, nothing is".

Some see beauty in mathematical results that establish connections between two areas of mathematics that at first sight appear to be unrelated. These results are often described as deep. One example are often cited is Euler's identity:

This is a special case of Euler's formula which states that, for any real number x,

Modern examples include the modularity theorem, which establishes an important connection between elliptic curves and modular forms (work on which led to the awarding of the Wolf Prize to Andrew Wiles and Robert Langlands), and "monstrous moonshine", which connects the Monster group to modular functions via string theory for which Richard Borcherds was awarded the Fields Medal.

An example of mathematical elegance is Leibnitz's series:

|

|

|

BIG NUMBERS See http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/mar/25/trillion-dollar-rescue-plan

MATH TERMS See http://www.cut-the-knot.org/glossary/stop.shtml

Repunits are numbers where all digits are the same, and were named repunits by Albert Beiler.

In particular, the decimal (base-10) repunits that are often referred to as simply repunits are defined as

Repunits

![]() therefore have exactly

therefore have exactly

![]() decimal digits.

decimal digits.

Amazingly, the squares of the repunits

![]() give the

Demlo numbers,

give the

Demlo numbers,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() Ramchandra Dattaraya Kaprekar (1905–1986) studied the

Demlo numbers, named after a

train station 30 miles from Bombay on the then

G. I. P. Railway

where he had the idea of studying them.

These are the numbers 1, 121, 12321, …,

which are the squares of the

repunits 1,

11, 111, ….

He was an

Indian

recreational mathematician

who described several

classes of natural numbers

including the

Kaprekar,

Harshad

and

Self numbers

and discovered the

Kaprekar constant,

named after him. Despite having no formal postgraduate training and working

as a schoolteacher, he published extensively and became well known in

recreational mathematics circles.

The following table contains some repunits.

Ramchandra Dattaraya Kaprekar (1905–1986) studied the

Demlo numbers, named after a

train station 30 miles from Bombay on the then

G. I. P. Railway

where he had the idea of studying them.

These are the numbers 1, 121, 12321, …,

which are the squares of the

repunits 1,

11, 111, ….

He was an

Indian

recreational mathematician

who described several

classes of natural numbers

including the

Kaprekar,

Harshad

and

Self numbers

and discovered the

Kaprekar constant,

named after him. Despite having no formal postgraduate training and working

as a schoolteacher, he published extensively and became well known in

recreational mathematics circles.

The following table contains some repunits.

| 3 x 37 = 111 6 x 37 = 222 9 x 37 = 333 12 x 37 = 444 15 x 37 = 555 18 x 37 = 666 21 x 37 = 777 24 x 37 = 888 27 x 37 = 999 |

1 x 1 = 1 11 x 11 = 121 111 x 111 = 12321 1111 x 1111 = 1234321 11111 x 11111 = 123454321 111111 x 111111 = 12345654321 1111111 x 1111111 = 1234567654321 11111111 x 11111111 = 123456787654321 111111111 x 111111111=12345678987654321 |

1 x 9 + 2 = 11 12 x 9 + 3 = 111 123 x 9 + 4 = 1111 1234 x 9 + 5 = 11111 12345 x 9 + 6 = 111111 123456 x 9 + 7 = 1111111 1234567 x 9 + 8 = 11111111 12345678 x 9 + 9 = 111111111 123456789 x 9 +10= 1111111111 |

| 2519 Mod 2 = 1 2519 Mod 3 = 2 2519 Mod 4 = 3 2519 Mod 5 = 4 2519 Mod 6 = 5 2519 Mod 7 = 6 2519 Mod 8 = 7 2519 Mod 9 = 8 2519 Mod 10 = 9 |

0 x 9 + 8 = 8 9 x 9 + 7 = 88 98 x 9 + 6 = 888 987 x 9 + 5 = 8888 9876 x 9 + 4 = 88888 98765 x 9 + 3 = 888888 987654 x 9 + 2 = 8888888 9876543 x 9 + 1 = 88888888 98765432 x 9 + 0 = 888888888 987654321 x 9 - 1 = 8888888888 9876543210 x 9 - 2 = 88888888888 |

1 x 8 + 1 = 9 12 x 8 + 2 = 98 123 x 8 + 3 = 987 1234 x 8 + 4 = 9876 12345 x 8 + 5 = 98765 123456 x 8 + 6 = 987654 1234567 x 8 + 7 = 9876543 12345678 x 8 + 8 = 98765432 123456789 x 8 + 9 = 987654321 |

|

|

142857 x 2 = 285714 142857 x 3 = 428571 142857 x 4 = 571428 142857 x 5 = 714285 142857 x 6 = 857142 |

|

91 |

times | 1 | = | 0 | 9 | 1 | 7x7=49 |

| 91 | times | 2 | = | 1 | 8 | 2 | 67x67=4489 |

| 91 | times | 3 | = | 2 | 7 | 3 | 667x667=44889 |

| 91 | times | 4 | = | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6667x6667=44448889 |

| 91 | times | 5 | = | 4 | 5 | 5 | 66667x66667=4444488889 |

| 91 | times | 6 | = | 5 | 4 | 6 | 666667x666667=444444888889 |

| 91 | times | 7 | = | 6 | 3 | 7 | 6666667x6666667=44444448888889 |

| 91 | times | 8 | = | 7 | 2 | 8 | etc. |

| 91 | times | 9 | = | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| 1x9+2 = 11 | 9 x 9 + 7 = 88 | 9 x 9 = 81 | 6 x 7 = 42 |

| 12x9+3 = 111 | 98 x 9 + 6 = 888 | 99 x 99 = 9801 | 66 x 67 = 4422 |

| 123x9+4 = 1111 | 987 x 9 + 5 = 8888 | 999 x 999 = 998001 | 666 x 667 = 444222 |

| 1234x9+5 = 11111 | 9876 x 9 + 4 = 88888 | 9999 x 9999 = 99980001 | 6666 x 6667 = 44442222 |

| 12345x9+6 = 111111 | 98765 x 9 + 3 = 888888 | etc | etc |

| 123456x9+7 = 1111111 | 987654 x 9 +2 = 8888888 | ||

| 1234567x9+ = 11111111 | 9876543x9+1= 88888888 | ||

| 12345678x9+9=111111111 | 98765432x9 = 888888888 |

| 1x1=1 | 4x4=16 |

| 11x11=121 | 34x34=1156 |

| 111x111=12321 | 334x334=111556 |

| 1111x1111=1234321 | 3334x3334=11115556 |

| 11111x11111=123454321 | 33334x33334=1111155556 |

| 111111x111111=12345654321 | etc. |

| 1111111x1111111=1234567654321 | |

| 11111111x11111111=123456787654321 | |

| 111111111x111111111=12345678987654321 |

Santa's Options Assuming Rudolph was in front, there are 40,320 ways to arrange the other eight reindeer.

Geometry

Are the eight balls

moving in a circle or a straight line?

http://showyou.com/v/y-pNe6fsaCVtI/crazy-circle-illusion?u=multimotion

Roman Numerals The original Roman year had 10 named months Martius "March", Aprilis "April", Maius "May", Junius "June", Quintilis "July", Sextilis "August", September "September", October "October", November "November", December "December", and probably two unnamed months in the dead of winter when not much happened in agriculture. The year began with Martius "March". Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome circa 700 BC, added the two months Januarius "January" and Februarius "February". He also moved the beginning of the year from Marius to Januarius and changed the number of days in several months to be odd, a lucky number. After Februarius there was occasionally an additional month of Intercalaris "intercalendar". This is the origin of the leap-year day being in February. In 46 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the Roman calendar (hence the Julian calendar) changing the number of days in many months and removing Intercalaris.

The numerals are: 1=I (unus); 5=V (quinque); 10=X (decem); C=100 (centum), and M=1000 (mille). They also used 50=L (quinquaginta); and 500=D (quingenti).

When a small number comes before a larger number, the smaller number is subtracted. 4 = IV or 5-1. When a smaller number follows a larger one, the two are added together: 7 = VII, or 5 + 2 and 19 = XIX, or 10 + 9. Although the Romans used a decimal system for whole numbers, they used a duodecimal system for fractions because the divisibility by 12 made it easier to handle the common fractions of 1/3 and 1/4.

Chinese Multiplication See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8iIU9EDC2GQ and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=maRN2fUOF0o

Leonhard Euler (1707-1783): One of his

many contributions was called "Euler's Formula". The formula

states that, for any real number x,

![]() where e is the base of the natural logarithm, i is the

imaginary unit, and cos and sin are the trigonometric functions, with the

argument x given in radians. The formula is still valid if x

is a complex number. Richard Feynman called Euler's formula "our jewel"

and "one of the most remarkable, almost astounding, formulas in all of

mathematics".

where e is the base of the natural logarithm, i is the

imaginary unit, and cos and sin are the trigonometric functions, with the

argument x given in radians. The formula is still valid if x

is a complex number. Richard Feynman called Euler's formula "our jewel"

and "one of the most remarkable, almost astounding, formulas in all of

mathematics".

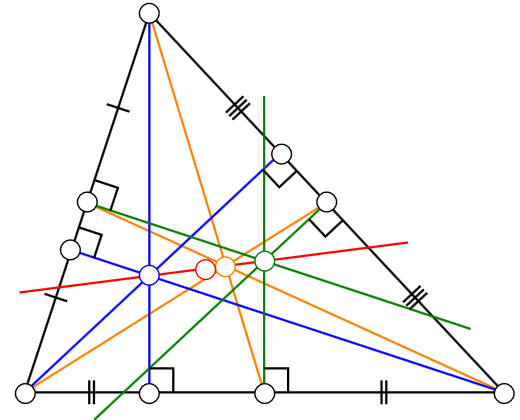

Euler Line

In the 18th century, the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler noticed that three of the centers of a triangle are always collinear (they always lie on a straight line). The three centers that have this surprising property are the triangle's centroid (where the three medians of the triangle's sides meet), circumcenter (where the perpendicular bisectors of the triangle's sides meet) and the orthocenter (where the three altitudes to the vertices of the triangle meet). The distance from the orthocenter to the centroid is two times the distance from the centroid to the circumcenter. (Another center, the incenter, where the bisectors of the three angles meet, is not on this line.)

|

| Acute Triangle |

|

| Obtuse Triangle |

|

| Equilateral Triangle |

|

Incenter Located at intersection of the angle bisectors. |

|

Centroid Located at intersection of the medians |

|

Circumcenter Located at intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of the sides |

|

Orthocenter Located at intersection of the altitudes |

|

|

The medians meet the circumcircle of triangle ABC at A' , B' and C' . Let DEF be the triangle formed by the tangents at A, B, and C to the circumcircle of triangle ABC. The lines through DA' , EB' and FC' meet at the Exeter point |

|

The points of intersection of the adjacent

angle trisectors of the

angles of any

triangle

|

|

The nine-point circle is a

circle through nine points: The midpoint of each side of the triangle. The foot of each altitude The midpoint of the line segment from each vertex of the triangle to the orthocenter.

|

|

Nine Point Circle above |

|

|

The Euler line in any non equilateral

triangle

passes through five points: The orthocenter, the circumcenter, the centroid, the Exeter point and the center of the nine-point circle of the triangle. The Exeter Point is not shown on the left. |

| Orthocenter (Blue), Incenter (Orange), Circumcircle (Green), Center of the Nine point circle (Red) |

Euler Line in red |

Euler and the Nine Point Circle

The nine-point circle is a circle that can be constructed for any given triangle. It is so named because it passes through nine significant concyclic points defined from the triangle. These nine points are:

| The midpoint of each side of the triangle | |

| The foot of each altitude | |

| The midpoint of the line segment from each vertex of the triangle to the orthocenter (where the three altitudes meet; these line segments lie on their respective altitudes). |

The nine-point circle is also known as Feuerbach's circle, Euler's circle, and Terquem's circle.

To construct the nine point circle of a triangle, see http://jwilson.coe.uga.edu/EMT668/EMT668.Folders.F97/Anderson/geometry/geometry1project/construction/construction.html

.1. Draw a triangle ABC and construct the midpoints of the three sides. Label them as L, M, N.

2. Construct the feet of the altitudes of the triangle ABC. Label them as D, E, F. Label the point of intersection of the three altitudes as H. This is also called the orthocenter.

3. Construct the midpoints of the segments AH, BH, CH. Label them as X, Y, Z.

4. Notice the nine points, L,M,N,D,E,F,X,Y, Z, lie in a circle called the Nine-Point Circle..

5. Construct the circumscribed circle for triangle LMN. Label the center of that circle U.

The center U of the circumscribed circle for triangle LMN will also be the center of the Nine-Point Circle.

More on Nine-Point Circle at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_center where we learn the following:

Let A, B,

C denote the vertex angles of the reference triangle, and let x : y : z be a variable point in trilinear coordinates; then an equation for the Euler line is| Center | Trilinear Coordiates | On Euler Line? |

| Orttocenter | Secant A: Secant B : Secant C | Yes |

| Centroid | Cosecant A: Cosecant B: Cosecant C | Yes |

| Circumcenter | Cosine A: Cosine B: Cosine C | Yes |

| Nine Point Circle | Cosine (B - C): Cosine (C - A): Cosine (A - B) | Yes |

| In Center | 1:1:1 | Only if Isosceles |

Euler and polyhedrons

A platonic solid is a regular, convex polyhedron with congruent faces of regular polygons and the same number of faces meeting at each vertex. There are five regular polyhedrons that meet those criteria, and each is named after its number of faces.:

| Tetrahedron | Hexahedron | Octahedron | Dodecahedron | Icosahedron |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 Triangles | 4 Squares | 8 Triangles | 12 Pentagons | 20 Triangles |

Euler's formula for polyhedrons is: V - E + F = 2 That is the number of vertices, minus the number of edges, plus the number of faces, is equal to two.

More on Euler

In analytical mathematics, Euler's identity (also known as Euler's equation) is the equality:

| eiπ + 1 = 0 |

| e is Euler's number, the base of natural logarithms |

| i is the imaginary unit, which satisfies i2 = −1 |

| π is pi, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter |

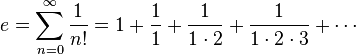

Euler's number e is an important mathematical constant, approximately equal to 2.71828, that is the base of the natural logarithm. It is the limit of (1 + 1/n)n as n becomes large, an expression that arises in the study of compound interest, and can also be calculated as the sum of the infinite series:

e is the unique real number such that the value of the derivative (slope of the tangent line) of the function f(x) = ex at the point x = 0 is equal to 1. The function ex so defined is called the exponential function, and its inverse is the natural logarithm, or logarithm to base e.

The number e is of eminent importance in mathematics, alongside 0, 1, π and i. All five of these numbers play important and recurring roles across mathematics, and are the five constants appearing in one formulation of Euler's identity. Like the constant π, e is irrational: it is not a ratio of integers; and it is transcendental: it is not a root of any non-zero polynomial with rational coefficients. The numerical value of e truncated to 50 decimal places is 2.71828182845904523536028747135266249775724709369995...

e and compound interest

Let ![]() be the

principal (initial investment),

be the

principal (initial investment), ![]() be

the annual compounded rate,

be

the annual compounded rate, ![]() the

"nominal rate,"

the

"nominal rate," ![]() be

the number of times

interest is compounded per year (i.e.,

the year is divided into

be

the number of times

interest is compounded per year (i.e.,

the year is divided into ![]() conversion

periods), and

conversion

periods), and ![]() be

the number of years (the "term"). The

interest rate per

conversion period is then

be

the number of years (the "term"). The

interest rate per

conversion period is then

|

|

If interest is compounded ![]() times

at an annual rate of

times

at an annual rate of ![]() (where,

for example, 10% corresponds to

(where,

for example, 10% corresponds to ![]() ),

then the effective rate over

),

then the effective rate over ![]() the

time (what an investor would earn if he did not redeposit his interest after

each compounding) is

the

time (what an investor would earn if he did not redeposit his interest after

each compounding) is

|

|

The total amount of holdings ![]() after

a time

after

a time ![]() when

interest is re-invested is then

when

interest is re-invested is then

|

|

Note that even if interest is compounded continuously, the return is still finite since

|

|

where e is the base of the natural logarithm.

The time required for a given

principal to double (assuming ![]() conversion period) is given by solving

conversion period) is given by solving

|

|

|

|

where ln is the natural logarithm. This function can be approximated by the so-called rule of 72:

|

|

NUMBER THEORY

Numbers are classified according to type. The first type of number is the first type you ever learned about: the counting, or "natural" numbers:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ...

The next type is the "whole" numbers, which are the natural numbers together with zero:

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ...

Then come the "integers", which are zero, the natural numbers, and the negatives of the naturals:

... -6, -5, -4, -3, -2, -1, 9, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ...

The next type is the "rational", or fractional, numbers, which are technically regarded as ratios (divisions) of integers. In other words, a fraction is formed by dividing one integer by another integer.

Sums of Natural Numbers The sum of the first n natural numbers is: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 ....... + n = n(n+1)/2 Gauss developed this formula when in primary school: the average of the first number and the last number times the number of numbers! If n = 6: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 = 21 = (6x7)/2

Sums of Even Numbers The sum of the first k even natural numbers is: 2 + 4 + 6 ..... + 2k = k(k+1). If k = 3: 2 + 4 + 6 = 12 = (3x4)

Sums of Odd Numbers The sum of the first k odd natural numbers is: 1 + 3 + 5 ..... + (2k - 1) = k2 If k = 3: 1 + 3 + 5 = 9 = (3x3)

Sums of Squares The sum of the squares of

the first n natural numbers is:

30 = (12 + 22 + 32 + 42) = 1 + 4 + 9 + 16

Also see: http://www.takayaiwamoto.com/Sums_and_Series/sumsqr_1.html and http://www.math.utah.edu/~palais/sums.html

365 = ( 102 + 112 + 122) = (132 + 142)

Sums of Cubes The sum of the cubes of the first n natural numbers is:

Divisor Function: D(x) = number of divisors in a number including 1 and x. If m and n are relatively prime, then D(mn) = D(m) x D(n)

|

m |

n |

mn |

D(m) |

D(n) |

D(mn) = D(m) x D(n) |

Divisors |

|

2 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

1, 2, 3, 6 |

|

4 |

9 |

36 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12,18, 36 |

| 15 | 1 | 15 | 4 |

1 |

4 |

1, 3, 5, 15 |

|

28 |

1 |

28 |

6 |

1 |

6 |

1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28 |

| 15 | 28 | 420 | 6 | 4 | 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 12, 14, 15, 20, 21, 28, 30, 35, 42, 60, 70, 84, 105, 140, 210, 420 |

Take any integer. Examples: 15 and 28. Write its factors. Underneath each factor write the D(x) for each factor:

| Factors of 15 | 15 | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||

| D(Factors of 15) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Factors of 28 | 28 | 14 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| D(Factors of 28) | 6 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Liouville's Theorem says: The sum of the cubes of the numbers in the second line equals the square of the sum of those same numbers: 64 + 8 + 8 + 1 = 81. 4 + 2 + 2 + 1 = 9, and 9 squared = 81. The sum of the cube of the numbers in the fourth line equals the square of the sum of those same numbers: 216 + 64 + 8 + 27 + 8 + 1 = 324. 6 + 4 + 2 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 18, and18 squared = 324.

Conjecture is: Pick small numbers and the sum of their cubes is less than the square of their sums. But if you pick large numbers the converse is true. See examples using four numbers are below:

| Their Sum | Square of their Sum | Sum of their Cubes | Square of their Sum minus the Sum of their Cubes | |||||

| A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 36 | 30 | 6 |

| B | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 36 | 18 | 18 |

| C | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 121 | 107 | 14 |

| D | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 81 | 81 | 0 |

| E | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 81 | 135 | -54 |

| F | 1 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 17 | 289 | 737 | -448 |

| G | 3 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 24 | 576 | 1098 | -522 |

In a 1749 report, Leonhard Euler admits that the series diverges but prepares to sum it anyway:

...when it is said that the sum of this series 1−2+3−4+5−6 etc. is 1⁄4, that must appear paradoxical. For by adding 100 terms of this series, we get −50, however, the sum of 101 terms gives +51, which is quite different from 1⁄4 and becomes still greater when one increases the number of terms. But I have already noticed at a previous time, that it is necessary to give to the word sum a more extended meaning....

Euler proposed a generalization of the word "sum" several times; see Euler on infinite series. In the case of 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ..., his ideas are similar to what is now known as Abel summation:

...it is no more doubtful that the sum of this series 1−2+3−4+5 + etc. is 1⁄4; since it arises from the expansion of the formula 1⁄(1+1)2, whose value is incontestably 1⁄4. The idea becomes clearer by considering the general series 1 − 2x + 3x2 − 4x3 + 5x4 − 6x5 + &c. that arises while expanding the expression 1⁄(1+x)2, which this series is indeed equal to after we set x = 1.

There are many ways to see that, at least for absolute values |x| < 1, Euler is right in that

![]()

One can take the Taylor expansion of the right-hand side, or apply the formal long division process for polynomials. Starting from the left-hand side, one can follow the general heuristics above and try multiplying by (1+x) twice or squaring the geometric series 1 − x + x2 − .... Euler also seems to suggest differentiating the latter series term by term.

In the modern view, the series 1 − 2x + 3x2 − 4x3 + ... does not define a function at x = 1, so that value cannot simply be substituted into the resulting expression. Since the function is defined for all |x| < 1, one can still take the limit as x approaches 1, and this is the definition of the Abel sum:

Leonhard Euler is most famous for the

"Euler Identity":

![]() The special case, with x =

π

gives the beautiful identity:

The special case, with x =

π

gives the beautiful identity:

![]() ,

which involves 0, 1, i, e and

π.

,

which involves 0, 1, i, e and

π.

The numbers which can be arranged in a compact triangular pattern are termed as triangular numbers. The triangular numbers are formed by partial sum of the series 1+2+3+4+5+6+7......+n. So

T1 = 1

T2 = 1 + 2 = 3

T3 = 1 + 2 + 3 = 6

T4 = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = 10

So the nth triangular number can be obtained as Tn = n(n+1)/2, where n is any natural number. In other words triangular numbers form the series 1,3,6,10,15,21,28.....

n2 = the sum of two consecutive triangular numbers, because Tn + Tn-1 = n(n+1)/2 + (n-1)(n)/2 = n2

Cubics, Quartics, and Quintics

| Niccolo Tartaglia, who solved the cubic, failed miserably for the rest of his life (mainly because he spent it trying to discredit Cardano). See http://www.storyofmathematics.com/16th_tartaglia.html |

| Giralamo Cardano, who stole Tartaglia's solution, is also credited with solving the cubic. |

| Lodovico Ferrara, solved the general quartic, was poisoned, probably by his sister, over an inheritance dispute. |

| Evariste Galois, who showed the general quintic was unsolvable, died in a duel at the age of 29. |

| Niels Henrik Abel, who duplicated and extended Galois' proof independently, finally managed to receive his first faculty position. The notification letter arrived a few days after Abel had died of pneumonia. He was 29. |

Brocard's Problem: N factorial + 1 = X squared. This is true for X = 5, 11, and 71, but that may be all. Pierre Rene Jean Baptiste Henri Brocard: (1845 - 1922). Bruce Berndt and William Galway used a computer in 2000 to show there are no other solutions up to N = one billion.

Primes, other than 2 or 3 are either of the form 6n + 1 or 6n - 1.

Lychrel Numbers. Most numbers become a palindrome by reversing their digits and adding repeatedly. (349 + 943 = 1292, 1292 + 2921 = 4213, 4213 + 3124 = 7337 a palindrome. Those that do not convert, are Lychrel Numbers. The name "Lychrel" was coined by Wade Van Landingham: a rough anagram of his girlfriend's name Cheryl.

Catalan's conjecture (occasionally now referred to as Mihăilescu's theorem) was conjectured by the mathematician Eugene Charles Catalan in 1844 and proven in 2002 by Preda Mihăilescu.

To understand the conjecture, notice that 23 and 32 (i.e. 8 and 9) are two powers of natural numbers, whose values 8 and 9 respectively are consecutive. The conjecture states that this is the only case of two consecutive powers. That is to say, that the only solution in the natural numbers of

for x, a, y, b > 1 is x = 3, a = 2, y = 2, b = 3.

SQUARE ROOT The square root of the number 81 is 9. 81 is the only number whose square root is the sum of its digits.

What did Pythagoras say when he was first confronted with the square root of 2? "There has to be a rational explanation for this."

PARTITIONS See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partition_(number_theory)

In number theory and combinatorics, a partition of a positive integer n, also called an integer partition, is a way of writing n as a sum of positive integers. Two sums that differ only in the order of their summands are considered the same partition. If order matters, the sum becomes a composition. For example, 4 can be partitioned in five distinct ways:

The order-dependent composition 1 + 3 is the same partition as 3 + 1, while 1 + 2 + 1 and 1 + 1 + 2 are the same partition as 2 + 1 + 1.

A summand in a partition is also called a part. The number of partitions of n is given by the partition function p(n). So p(4) = 5. The notation λ ⊢ n means that λ is a partition of n.

Partitions can be graphically visualized with Young diagrams (boxes) or Ferrers diagrams (dots). They occur in a number of branches of mathematics and physics, including the study of symmetric polynomials, the symmetric group and in group representation theory in general.

Young diagrams associated to the partitions of the positive integers 1 through 8. They are arranged so that images under the reflection about the main diagonal of the square are conjugate partitions. (below)

GAMMA FUNCTION

The (complete) gamma function

![]() is defined to be an extension of the

factorial to

complex and

real number arguments. It is related to the

factorial by

is defined to be an extension of the

factorial to

complex and

real number arguments. It is related to the

factorial by

![]() a slightly unfortunate notation due to Legendre which is now universally

used instead of Gauss's simpler

a slightly unfortunate notation due to Legendre which is now universally

used instead of Gauss's simpler

![]() There are no points

There are no points

![]() at which

at which

![]() .

.

The gamma function can be defined as a

definite integral

for ![]() (Euler's

integral form) as

(Euler's

integral form) as

![]() or

or ![]() or

or ![]()

The complete gamma function ![]() can

be generalized to the upper

incomplete gamma function

can

be generalized to the upper

incomplete gamma function ![]() and

lower

incomplete gamma function

and

lower

incomplete gamma function ![]() .

.

|

|

Plots of the real and imaginary parts of ![]() in

the complex plane are illustrated above.

in

the complex plane are illustrated above.

Below we see the gamma function along part of the real axis:

Integrating ![]() =

= ![]() by

parts for a

real argument, it can be seen that

by

parts for a

real argument, it can be seen that ![]() =

= ![]()

If ![]() is

an

integer

is

an

integer ![]() =

= ![]() so

the gamma function reduces to the

factorial for a

positive integer argument.

so

the gamma function reduces to the

factorial for a

positive integer argument.

A beautiful relationship between ![]() and

the

Riemann zeta function

and

the

Riemann zeta function ![]() is

given by:

is

given by:

![]() for

for ![]()

The gamma function can also be defined by an infinite product form:

![]() where

where ![]() is

the

Euler-Mascheroni constant

is

the

Euler-Mascheroni constant

The Euler limit form is ![]() so,

so, ![]() =

= ![]()

The reciprocal of the gamma function ![]() is

an

entire function expressed as

is

an

entire function expressed as

![]()

where ![]() is

the

Euler-Mascheroni constant

and

is

the

Euler-Mascheroni constant

and ![]() is

the

Riemann zeta function

is

the

Riemann zeta function

|

|

This site was last updated 09/29/18