The

Merode Triptych was painted in or around 1427 through a commission

which was likely received by Robert Campin, and then passed to an

unknown collaborator1.

Departing from a tradition of illustrating notable scenes from

the lives of Jesus and Mary, the third panel of this Triptych is

instead a detailed depiction of Joseph, working alone in his shop.

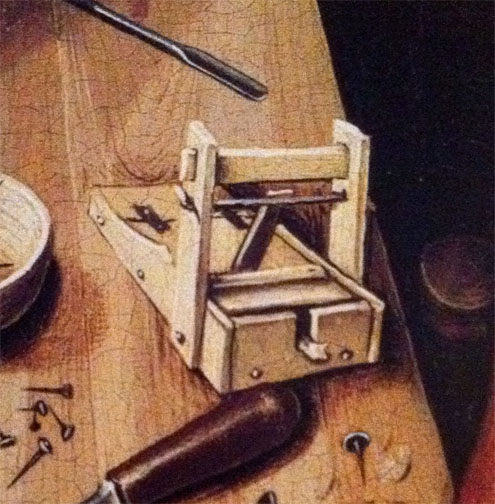

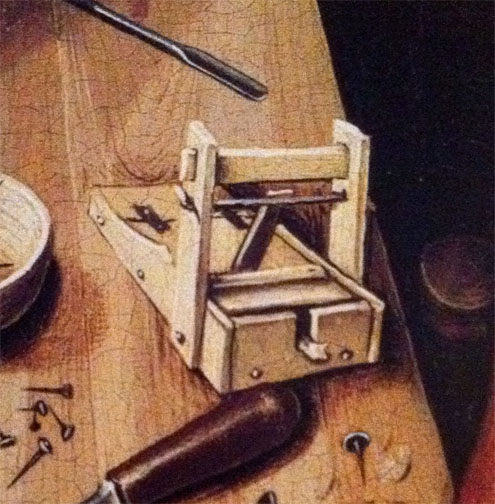

Amongst the tools and other items shown on his table is a

mousetrap, of the type described by Mascall in 1590 as a "following

trappe2." Although this item was once argued to be a carpenter's hand plane3,

the issue was resolved in 1966 by John Jacob, curator of the Walker Art

Gallery, Liverpool, when he commissioned a replica of the trap,

and used it to catch a mouse4.

Image from Web Gallery of Art

Although

the artist's representation of the trap is imperfect, as such things so

often are, it is nonetheless remarkable for its detail which allows key

features and functions to be identified. The basic form of the

trap is a box with a hinged lid. A torsion-sprung paddle, known

as a "follower5," is

positioned above the lid to drive it downward and to then hold it

closed. A trigger mechanism is hinted at by a square peg

extending from a slot near the base of the box. Rather than being

carefully joined, the box is simply nailed together as would be

appropriate for such a crude appliance, and as evidenced by the visible

nail heads and by the loose nails and hammer strewn about the table.

Hinges, mortised beam, and a conventionally pegged torsion

bundle, are all clearly shown. The paleness of the trap amongst

the darker table top and tool handles suggests that it is new or under

construction, and a second mousetrap displayed on the windowsill

confirms that these are indeed subjects of Joseph's handiwork.

What

the artist omits is any form of a trigger. When first observing

this painting, I incorrectly assumed that the trigger was therefore

internal, and that the square peg was an extension of a treadle which

must be manipulated to allow the trap to be "set." Being an

expert on modern trigger mechanisms6,

I envisioned a simple arrangement which accommodated these reasonable

assumptions. I have since come to learn that, although my

prospective design may have been superior to the trigger hastily

contrived by John Jacob for his earlier replica, I was no less

incorrect.

I had failed to notice at first that the

square treadle extension is apparently notched, or hooked, and I also

suffered under the unnecessary assumption that the trap, which after

all remained on the carpenter's worktable, was depicted as complete.

Further study led to the same conclusion which was generally

accepted in 1979 that the trap would have been fitted with an external

trigger of a type common to Medieval traps7, and described by Mascall as a "clicket8."

This device engages the notch in the treadle extension, and props

open the lid of the trap against the force exerted by the follower.

When the treadle is disturbed, the clicket is launched from this

position by the descending lid.

The Merode mousetrap was

expected to be non-lethal, as evidenced by the manner in which the

follower locks the closed lid against being opened from the inside.

This function also requires that the lid close completely, and so

precludes its use for crushing or impaling. Although the follower

does impart force to the lid to make it close faster, the result is not

particularly dangerous. I have sized this replica such that the

entire mouse, tail and all, should be safely inside when the lid drops.

Max

Written this seventh day of Aprill, 2011

1 DE VOS, D. 2002. "The Flemish Primitives." Princeton University.

2 MASCALL, L. 1590. "A booke of engines and traps to take polcats,

buzardes, rattes, mice and all other kindes of vermine and beasts

whatsoever, most profitable for all warriners, and such as delight in

this kinde of sport and pastime." John Wolfe, London. A facsimile

edition was published in 1973 by Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Ltd.,

Amsterdam and De Capo Press Inc., New York.

3 ZUPNICK, I. 1966. "The mystery of the Merode mousetrap." Burlington Magazine Vol. 108:126-133.

4 JACOB, J. 1966. The Merode mousetrap. Burlington Magazine 108:373-374.

5 MASCALL

6 I am. I totally am.

7 KLIJN, E.M.C.F. 1979. Ratten, muizen en mensen. Het Nederlands Openluchtmuseum, Arnhem.

8 MASCALL |